Articles

October 6, 2025

Saving what others throw away: Restare and the culture of upcycling

Interview with architect and founder of Restare, Khrystyna Badzian, on why old materials deserve a second life, and why rescuing them is a form of cultural resistance

Regularly ensure no new buildings or trees are casting shadows

Et tellus congue praesent pellentesque volutpat laoreet bibendum ut congue sed libero velit sed suscipit amet mattis orci aliquet egestas nibh quis neque vulputate convallis adipiscing magna. Mattis quisque in feugiat in metus laoreet sodales lectus id augue quis pellentesque feugiat luctus malesuada laoreet bibendum nibh augue fames feugiat diam sed. Varius ut eget sollicitudin sed semper sed semper sed nunc sagittis sit at sit.

- Euismod amet rutrum ornare egestas ac nunc ullamcorper mi pretium

- Mauris aliquet faucibus iaculis dui vitae litum sus ullamco

- Semper pharetra duis purus facilisis nec pretium imperdiet varius

- Molestie eget quis viverra eget eget pulvinar a donec vitae amet

Regularly check the energy output to identify any issues

Sed massa vestibulum lectus suspendisse egestas sit. Interdum vel scelerisque non imperdiet nec euismod enim tristique purus leo fames ut malesuada iaculis nunc ridiculus purus hendrerit mauris netus nunc arcu nulla hac parturient elementum proin. Malesuada commodo mi arcu sit adipiscing turpis nullam dignissim phasellus cras sagittis et sit blandit vestibulum vitae eget nulla vel dictum elementum in feugiat vel volutpat libero porta sed.

Have a professional periodically inspect and service the system

Nibh tellus arcu aliquam in pellentesque ultricies non nisi suspendisse laoreet est felis placerat bibendum nisl fermentum ut et eget lacus lectus aliquet egestas nullam suspendisse vulputate dictum tempus ullamcorper mattis ultrices suscipit ipsum vitae arcu est volutpat suscipit dolor gravida netus massa lacinia maecenas dictum facilisis eu.

- Ut est dui porttitor vitae diam cras faucibus urna diam proin ultrices

- Mauris aliquet faucibus iaculis dui vitae ullamco

- Sapien tempus nec scelerisque praesent mattis vitae commodo

- Justo at dictum fames condimentum nisl tellus mauris fermentum

Be cautious not to put stress on the panels

Nibh tellus arcu aliquam in pellentesque ultricies non nisi suspendisse laoreet est felis placerat bibendum nisl fermentum ut et eget lacus lectus aliquet egestas nullam suspendisse vulputate dictum tempus ullamcorper mattis ultrices suscipit ipsum vitae arcu est volutpat suscipit dolor gravida netus massa lacinia maecenas ictum facilisis eu.

“At scelerisque elementum vitae sed et posuere adipiscing est pulvinar id proin eget posuere odio dictumst mi interdum”

Prevent birds, rodents, and insects from nesting under panels

Sit nulla nec vitae odio orci phasellus metus diam leo est nisi morbi arcu vitae urna sit platea ligula non quis non aliquam in posuere mi egestas nunc ac vitae sed nunc auctor justo orci id ut neque ac nec. In quam eget volutpat urna consequat sit morbi tristique lobortis urna convallis lectus ac.

Follow all guidelines to maintain the warranty validity

Praesent magna turpis tellus nisl tortor est nisl nulla neque sed nisi enim cras in vitae aliquam. Posuere ultrices hac consectetur nulla odio at vitae egestas dis vestibulum risus amet viverra tortor tincidunt nascetur platea ultricies fermentum nibh nulla in lorem lectus adipiscing pretium sit condimentum nullam in eu in lorem cras proin.

“If you ask why we pull things out of dumpsters, there is only one answer: so they don’t disappear. There will be no second shipment of authenticity.”

In Ukraine, the past often ends up in the dumpster. A century of wars, demolitions, rushed renovations, and cheap substitutes has made historic materials a vulnerable species. Doors of solid wood, handmade tiles, carved window frames — objects that once gave cities character — are thrown away simply because new is faster, easier, and sometimes cheaper.

For the last six years, architect and designer Khrystyna Badzian has been fighting this quiet approach. Through her initiative Restare, she rescues old materials, restores them, and proves that a city’s cultural memory can be rebuilt and saved.

“It started as weekend raids,” Khrystyna laughs. “We drove around Lviv in our own cars, checking dumpsters. You wouldn’t believe the amount of furniture, carpets, and chandeliers thrown away before the Easter cleaning. Not trash — treasures.”

At first, it was a hobby. Then the rescued objects filled apartments, garages, and corridors. Restare turned into a workshop, and eventually — a full architectural bureau.

Now the process is organized:

- a Telegram channel, Rubbish Watcher,s alerts them about finds,

- contractors notify them when old buildings are dismantled,

- posters appeared on dumpsters: “Don’t throw it away — pass it on.”

Restoration means heavy lifting, night drives to demolition sites, months of drying, sanding, cataloguing, photographing, and the eternal risk: what if the piece breaks, warps, or turns into pure kitsch? But Khrystyna and her team have a lot of reasons to do that:

- Higher quality than modern equivalents. Work with historic buildings has shown Khrystyna that original materials — natural wood, handmade tiles, solid doors — often outperform contemporary substitutes. Many of these items were produced to last for decades, while numerous modern solutions lose their durability much faster.

- Authenticity cannot be replicated. Interiors that incorporate historic bricks, plaster or wooden elements have a visual depth and texture that mass-produced materials cannot provide. Authentic objects create spaces that are unique rather than easily reproducible, helping architectural and interior projects avoid uniformity.

- Proportions and craftsmanship of the past. Historic doors, windows, and furniture were designed with careful attention to proportion and decorative detail — qualities often absent in simplified contemporary equivalents. Such elements offer not only aesthetic value but also contribute to the perception of space in a way modern mass-market products rarely match.

- Preserving local identity. Architecture forms part of a city’s cultural memory. When original materials and details are completely replaced, the urban environment gradually loses its recognisable character. Reusing authentic elements maintains a visual connection to local history and supports continuity in the city’s appearance.

“Imagine Lviv without its historic silhouette. Imagine replacing St. Andrew’s Church with golden domes. The city would lose its face.”

Each recovered item undergoes a structured process: sorting by material type, cleaning, measuring, photographing, and cataloguing on the Restare website and social media platforms. In many cases, the cost of documentation exceeds the monetary value of the object itself — yet the goal is preservation, not profit.

The team works with a broad range of materials, from large interior elements to small hardware components such as nails and hinges. To assess usability, Restare applies an internal grading system from 2 to 5, taking into account the condition of the item, its rarity, and cultural or architectural value.

“Sometimes a piece is in perfect condition but has no character. Sometimes it’s damaged, but it’s so rare you would be crazy not to save it.”

Some items remain immaculate but lack uniqueness; others may be structurally damaged, yet represent rare examples of craftsmanship or historical design and therefore warrant restoration.

After missile strikes in Lviv, Restare received fragments of destroyed doors, frames, and windows. However, obtaining access to damaged architectural elements remains challenging due to the regulatory and bureaucratic constraints of Ukraine.

As a result, many potentially recoverable materials are lost during demolition and disposal — a missed opportunity for reuse and historical preservation.

Restare began without specialised restorers, a defined business model, or an established customer base. The only clear principle was that disposing of historically valuable materials was wasteful for the city and its cultural memory.

Over time, the team mastered restoration techniques, developed digital catalogues, and built a community of clients and partners. Today, Restare is considered one of the leading voices of architectural recycling and upcycling in Ukraine.

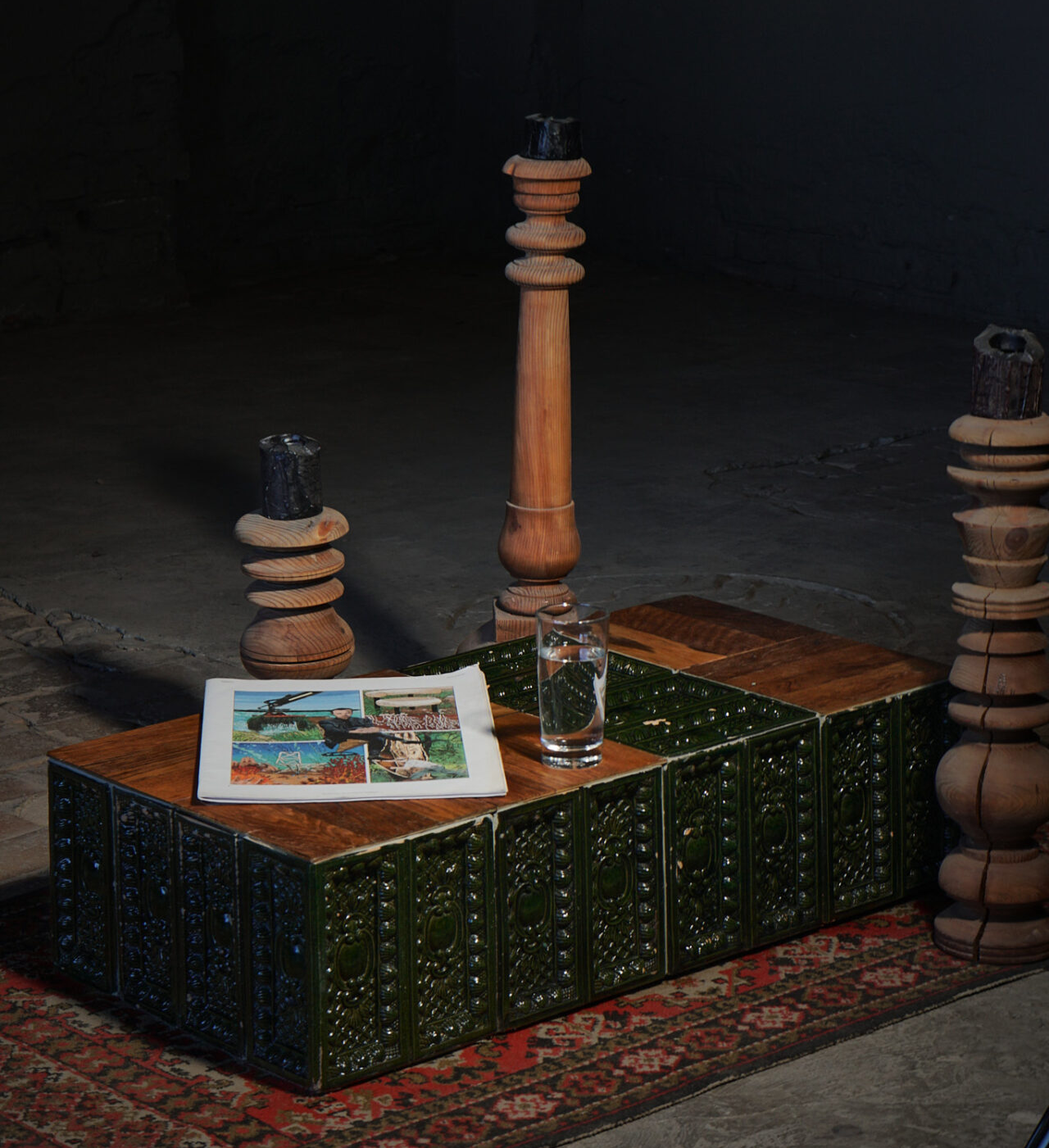

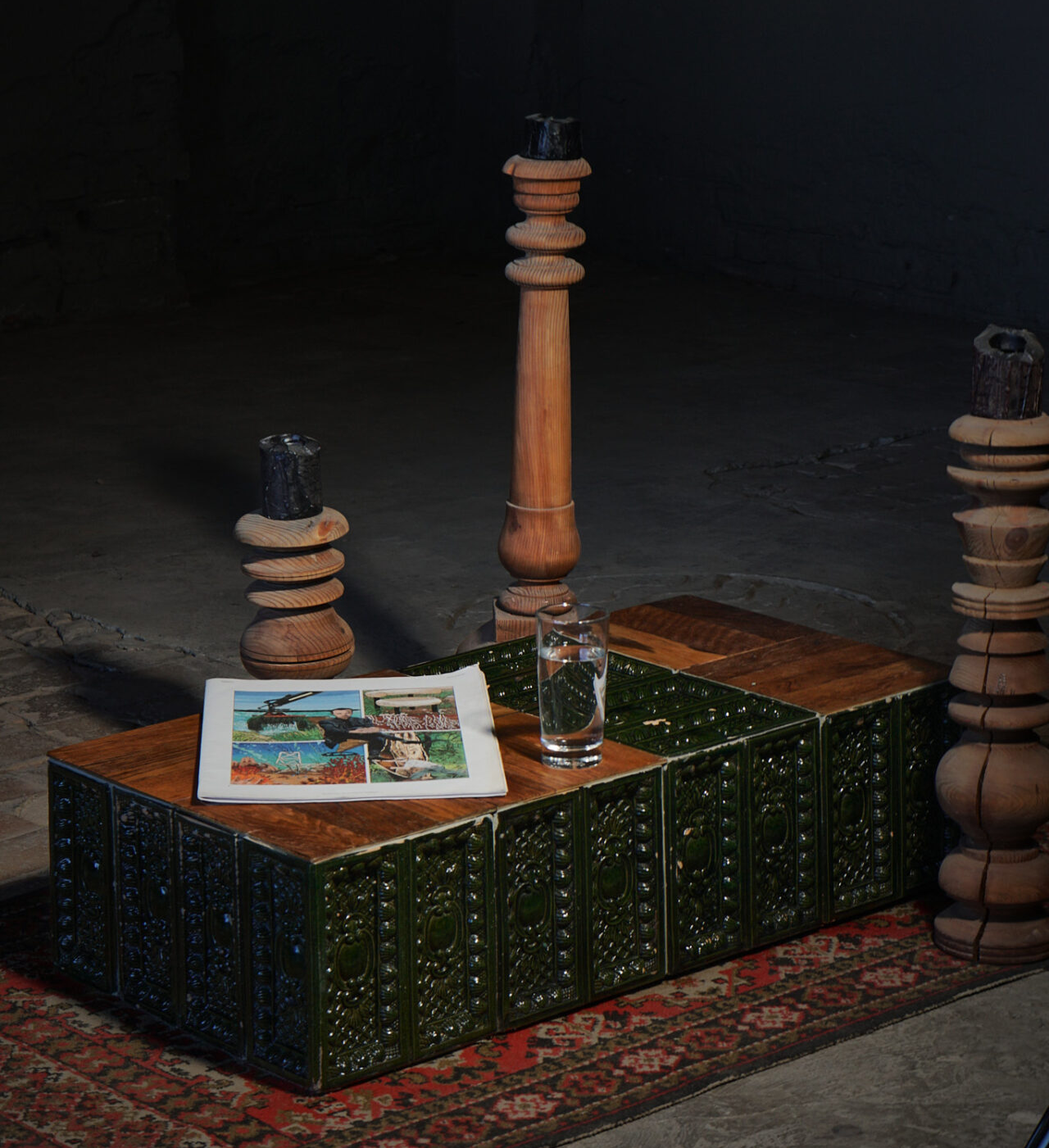

Their work demonstrates that restored objects can exist at the intersection of utility and art.

For example, a recently produced table made from reclaimed tiles functions as furniture, yet stands as a sculptural piece in its own right.

“You create something to endure longer than a single human lifetime, and a reminder of why preservation matters.”

“If you ask why we pull things out of dumpsters, there is only one answer: so they don’t disappear. There will be no second shipment of authenticity.”

In Ukraine, the past often ends up in the dumpster. A century of wars, demolitions, rushed renovations, and cheap substitutes has made historic materials a vulnerable species. Doors of solid wood, handmade tiles, carved window frames — objects that once gave cities character — are thrown away simply because new is faster, easier, and sometimes cheaper.

For the last six years, architect and designer Khrystyna Badzian has been fighting this quiet approach. Through her initiative Restare, she rescues old materials, restores them, and proves that a city’s cultural memory can be rebuilt and saved.

“It started as weekend raids,” Khrystyna laughs. “We drove around Lviv in our own cars, checking dumpsters. You wouldn’t believe the amount of furniture, carpets, and chandeliers thrown away before the Easter cleaning. Not trash — treasures.”

At first, it was a hobby. Then the rescued objects filled apartments, garages, and corridors. Restare turned into a workshop, and eventually — a full architectural bureau.

Now the process is organized:

- a Telegram channel, Rubbish Watcher,s alerts them about finds,

- contractors notify them when old buildings are dismantled,

- posters appeared on dumpsters: “Don’t throw it away — pass it on.”

Restoration means heavy lifting, night drives to demolition sites, months of drying, sanding, cataloguing, photographing, and the eternal risk: what if the piece breaks, warps, or turns into pure kitsch? But Khrystyna and her team have a lot of reasons to do that:

- Higher quality than modern equivalents. Work with historic buildings has shown Khrystyna that original materials — natural wood, handmade tiles, solid doors — often outperform contemporary substitutes. Many of these items were produced to last for decades, while numerous modern solutions lose their durability much faster.

- Authenticity cannot be replicated. Interiors that incorporate historic bricks, plaster or wooden elements have a visual depth and texture that mass-produced materials cannot provide. Authentic objects create spaces that are unique rather than easily reproducible, helping architectural and interior projects avoid uniformity.

- Proportions and craftsmanship of the past. Historic doors, windows, and furniture were designed with careful attention to proportion and decorative detail — qualities often absent in simplified contemporary equivalents. Such elements offer not only aesthetic value but also contribute to the perception of space in a way modern mass-market products rarely match.

- Preserving local identity. Architecture forms part of a city’s cultural memory. When original materials and details are completely replaced, the urban environment gradually loses its recognisable character. Reusing authentic elements maintains a visual connection to local history and supports continuity in the city’s appearance.

“Imagine Lviv without its historic silhouette. Imagine replacing St. Andrew’s Church with golden domes. The city would lose its face.”

Each recovered item undergoes a structured process: sorting by material type, cleaning, measuring, photographing, and cataloguing on the Restare website and social media platforms. In many cases, the cost of documentation exceeds the monetary value of the object itself — yet the goal is preservation, not profit.

The team works with a broad range of materials, from large interior elements to small hardware components such as nails and hinges. To assess usability, Restare applies an internal grading system from 2 to 5, taking into account the condition of the item, its rarity, and cultural or architectural value.

“Sometimes a piece is in perfect condition but has no character. Sometimes it’s damaged, but it’s so rare you would be crazy not to save it.”

Some items remain immaculate but lack uniqueness; others may be structurally damaged, yet represent rare examples of craftsmanship or historical design and therefore warrant restoration.

After missile strikes in Lviv, Restare received fragments of destroyed doors, frames, and windows. However, obtaining access to damaged architectural elements remains challenging due to the regulatory and bureaucratic constraints of Ukraine.

As a result, many potentially recoverable materials are lost during demolition and disposal — a missed opportunity for reuse and historical preservation.

Restare began without specialised restorers, a defined business model, or an established customer base. The only clear principle was that disposing of historically valuable materials was wasteful for the city and its cultural memory.

Over time, the team mastered restoration techniques, developed digital catalogues, and built a community of clients and partners. Today, Restare is considered one of the leading voices of architectural recycling and upcycling in Ukraine.

Their work demonstrates that restored objects can exist at the intersection of utility and art.

For example, a recently produced table made from reclaimed tiles functions as furniture, yet stands as a sculptural piece in its own right.

“You create something to endure longer than a single human lifetime, and a reminder of why preservation matters.”

Event Schedule

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur. Sit ut gravida aenean potenti. Metus in eu vel morbi dui nunc tellus. Non a massa maecenas massa.