Articles

August 14, 2025

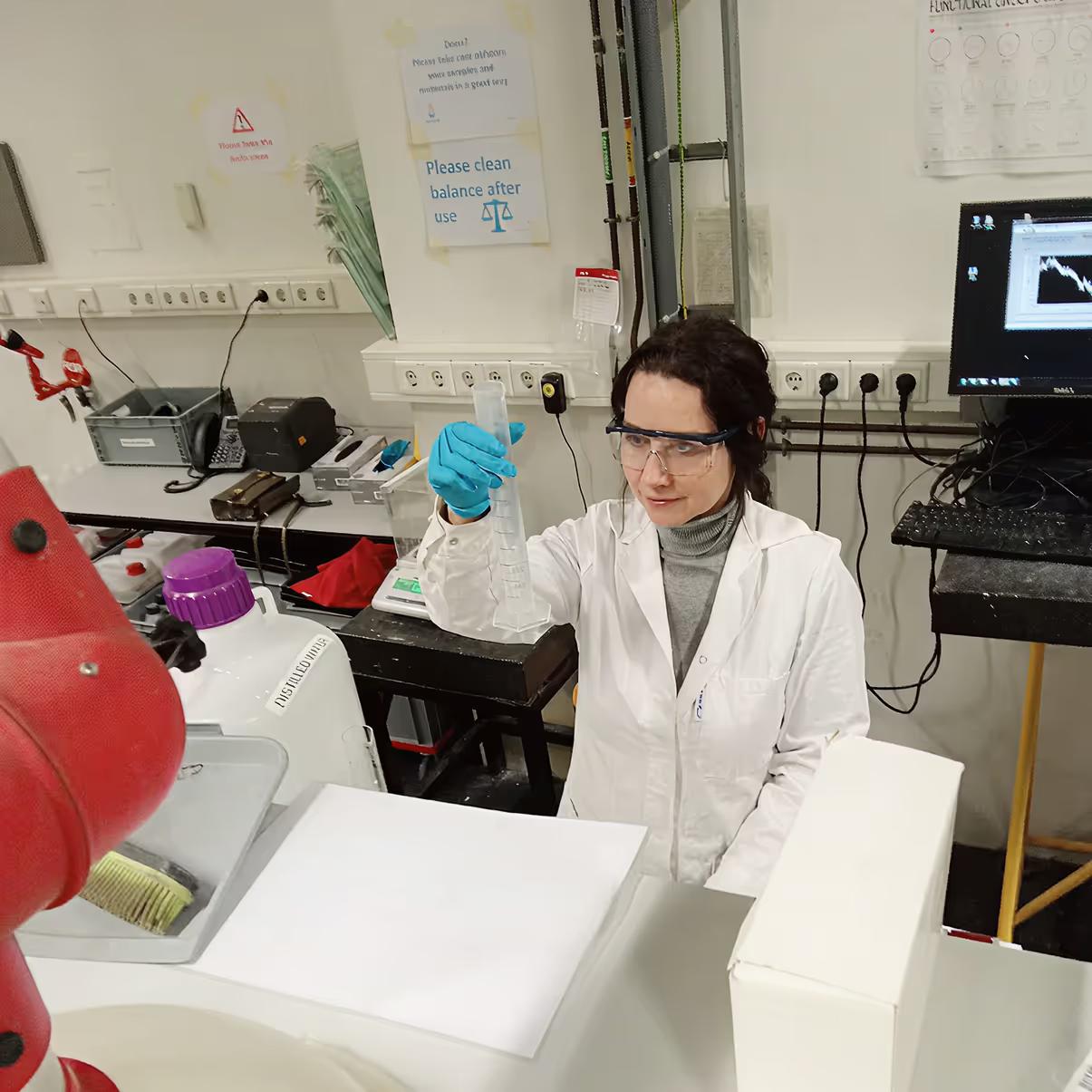

Constructing knowledge: the academic path of Nataliya Lushnikova

Interview with a researcher and lecturer at Eindhoven University of Technology

Regularly ensure no new buildings or trees are casting shadows

Et tellus congue praesent pellentesque volutpat laoreet bibendum ut congue sed libero velit sed suscipit amet mattis orci aliquet egestas nibh quis neque vulputate convallis adipiscing magna. Mattis quisque in feugiat in metus laoreet sodales lectus id augue quis pellentesque feugiat luctus malesuada laoreet bibendum nibh augue fames feugiat diam sed. Varius ut eget sollicitudin sed semper sed semper sed nunc sagittis sit at sit.

- Euismod amet rutrum ornare egestas ac nunc ullamcorper mi pretium

- Mauris aliquet faucibus iaculis dui vitae litum sus ullamco

- Semper pharetra duis purus facilisis nec pretium imperdiet varius

- Molestie eget quis viverra eget eget pulvinar a donec vitae amet

Regularly check the energy output to identify any issues

Sed massa vestibulum lectus suspendisse egestas sit. Interdum vel scelerisque non imperdiet nec euismod enim tristique purus leo fames ut malesuada iaculis nunc ridiculus purus hendrerit mauris netus nunc arcu nulla hac parturient elementum proin. Malesuada commodo mi arcu sit adipiscing turpis nullam dignissim phasellus cras sagittis et sit blandit vestibulum vitae eget nulla vel dictum elementum in feugiat vel volutpat libero porta sed.

Have a professional periodically inspect and service the system

Nibh tellus arcu aliquam in pellentesque ultricies non nisi suspendisse laoreet est felis placerat bibendum nisl fermentum ut et eget lacus lectus aliquet egestas nullam suspendisse vulputate dictum tempus ullamcorper mattis ultrices suscipit ipsum vitae arcu est volutpat suscipit dolor gravida netus massa lacinia maecenas dictum facilisis eu.

- Ut est dui porttitor vitae diam cras faucibus urna diam proin ultrices

- Mauris aliquet faucibus iaculis dui vitae ullamco

- Sapien tempus nec scelerisque praesent mattis vitae commodo

- Justo at dictum fames condimentum nisl tellus mauris fermentum

Be cautious not to put stress on the panels

Nibh tellus arcu aliquam in pellentesque ultricies non nisi suspendisse laoreet est felis placerat bibendum nisl fermentum ut et eget lacus lectus aliquet egestas nullam suspendisse vulputate dictum tempus ullamcorper mattis ultrices suscipit ipsum vitae arcu est volutpat suscipit dolor gravida netus massa lacinia maecenas ictum facilisis eu.

“At scelerisque elementum vitae sed et posuere adipiscing est pulvinar id proin eget posuere odio dictumst mi interdum”

Prevent birds, rodents, and insects from nesting under panels

Sit nulla nec vitae odio orci phasellus metus diam leo est nisi morbi arcu vitae urna sit platea ligula non quis non aliquam in posuere mi egestas nunc ac vitae sed nunc auctor justo orci id ut neque ac nec. In quam eget volutpat urna consequat sit morbi tristique lobortis urna convallis lectus ac.

Follow all guidelines to maintain the warranty validity

Praesent magna turpis tellus nisl tortor est nisl nulla neque sed nisi enim cras in vitae aliquam. Posuere ultrices hac consectetur nulla odio at vitae egestas dis vestibulum risus amet viverra tortor tincidunt nascetur platea ultricies fermentum nibh nulla in lorem lectus adipiscing pretium sit condimentum nullam in eu in lorem cras proin.

"The higher you climb in the construction field career, the fewer women you meet."

Dr. Nataliya Lushnikova is a researcher and educator dedicated to promoting gender equality in сonstruction. Her professional path spans multiple countries. She has taught in Ukraine, Poland, and Italy, collaborated with the environmental NGO EcoClub, received a scholarship through the Cambridge Colleges Hospitality Scheme, and participated in a United Nations Climate Conference.

She currently works at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e) in the Netherlands, having started her academic path in the Department of Building Materials in Rivne, Ukraine.

This text explores her journey, the challenges she has faced, and her reflections on the structural barriers and emerging opportunities for women in both the construction industry and academia.

Nataliya pursued a technical degree at the National University of Water and Environmental Engineering in Rivne, specializing in Technology of Building Structures, Products, and Materials. Although she faced gender stereotypes and academic challenges in this male-dominated field, she chose to continue her academic path by pursuing a PhD.

“I didn’t see myself in industry: on a cement plant or production line. But the department, where I could do research, felt like a safe space. That’s where my academic path began. I later got a job at the same university, occasionally taught abroad through grants, and eventually moved to the Netherlands in 2023.”

In Ukraine, teaching and research are intertwined; faculty members are expected to write textbooks and tutorials, develop course materials, conduct research, and publish scientific papers in addition to their regular teaching responsibilities.

By contrast, in the Netherlands and across much of the European Union, academic roles can be more specialized or prioritize research over teaching. Nataliya currently holds a postdoctoral research position — a role focused exclusively on research following the completion of a PhD, with no mandatory teaching duties.

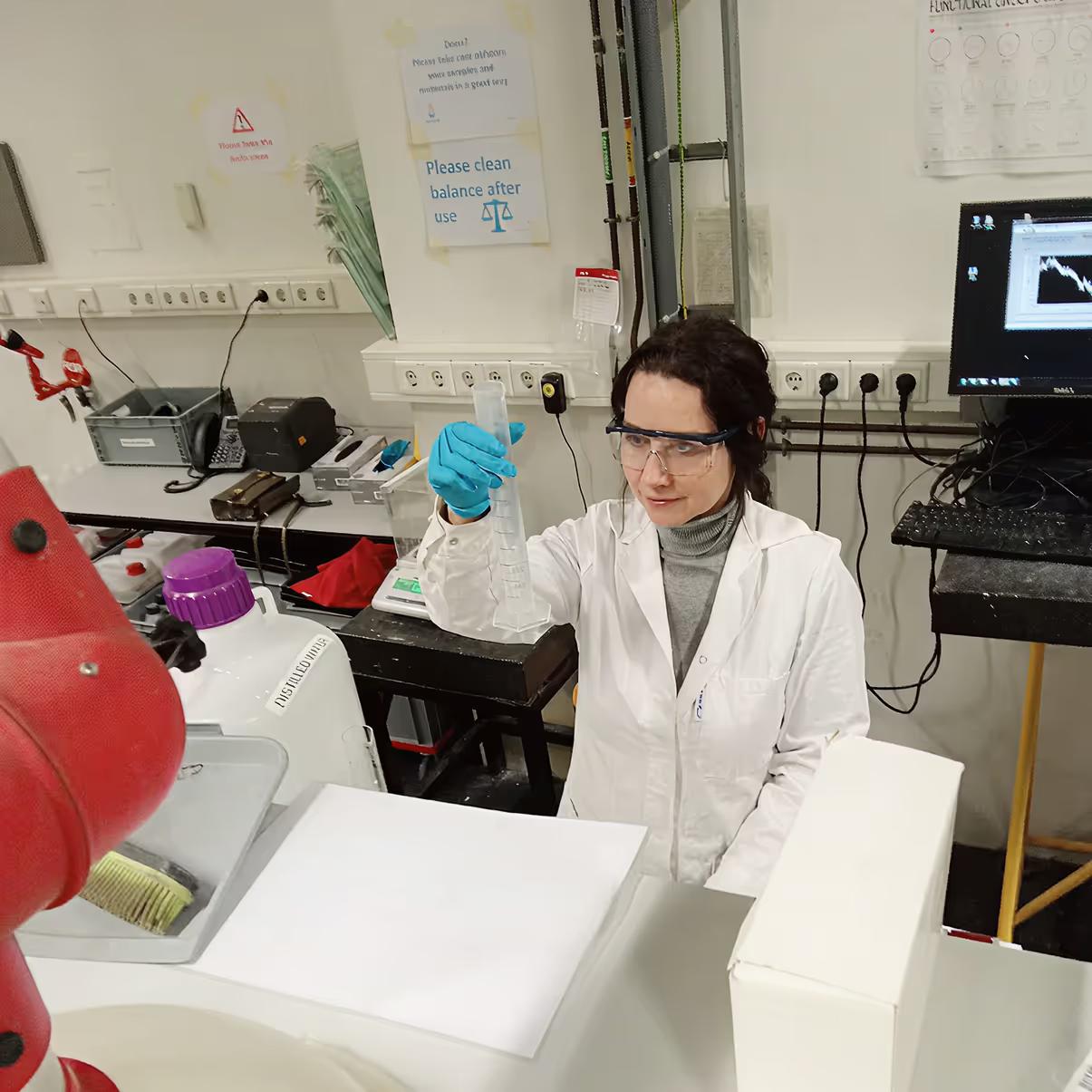

To be qualified for teaching in the Netherlands, she underwent a formal certification process that included pedagogical workshops, the development of a teaching portfolio, and delivering public lectures. While the process is more demanding compared with the Ukrainian experience, it offers significantly greater access to resources, advanced laboratory equipment, and opportunities for international collaboration.

“In the Netherlands, PhD candidates often outnumber faculty members. In Ukraine, it’s usually the opposite.”

Nataliya has encountered both implicit bias and structural barriers throughout her academic career.

“During my PhD, I was the only woman pursuing a technical doctorate within a predominantly male faculty and department,” she recalls. “Comments like, ‘Let the man attend the conference — we need more than just a smile there,’ were not uncommon. As a young female lecturer, I had fewer academic achievements compared to my more experienced male colleagues, which affected my teaching hours. After maternity leave, I was suggested to work part-time.”

She later joined an architecture department where women were better represented, which sparked her interest in gender-sensitive approaches to urban planning and universal design. However, the challenges didn’t disappear. When applying for postdoctoral positions, she was met with remarks such as:

“If you get the role, it’ll probably be because of gender quotas.”

Nataliya also notes that gender inequality is not always overt — it can manifest in physical, social, or institutional forms.

“Due to constant changes in university requirements, it took me several years to obtain the associate professor title. I completed the manuscript of the tutorial required to get this position just as my pregnancy reached full term. After giving birth, I kept revising the work — sometimes while carrying my baby up the stairs in a stroller, asking for help or leaving it outside.”

“In male-dominated sectors, women are expected to perform as if they have no other roles, as if being a mother isn't real work.”

While teaching a course on gender aspects in urban planning, Nataliya and her students explored an unexpected link between snowfall and male-centric city design.

"I showed the students a video about a small town in Sweden where, traditionally, snow removal started with the main roads — even though, statistically, those are mostly used by men. Women are more likely to walk, often with children, bags, or while accompanying elderly relatives, so snow-covered sidewalks and blocked public transport stops pose particular risks for them."

Nataliya notes that neighborhoods designed by women often prioritize safety and accessibility. One example is Frauen-Werk-Stadt, a gender-sensitive housing project in Vienna. And in the Netherlands, we see the approaches in urban design that meet the goals of universal accessibility.

Experience. Nataliya’s first step in overcoming impostor syndrome came through a Cambridge scholarship, international teaching experiences, and her work at EcoClub. Her resilience also grew during a visit to Brussels and at a UN conference alongside Ukrainian climate activists. These experiences proved that it’s worth taking on difficult — even intimidating — challenges. Especially those.

Mentorship. Support has been a key part of Nataliya’s academic journey: in Ukraine — through an informal mentor, and in the Netherlands — through colleagues, the Ukrainian community, and the WISE (Women in Science Eindhoven) network. WISE connects women at Eindhoven University of Technology — from PhD students to professors. At first, Nataliya attended events; later, she joined the Board and now helps organize them. Despite progress, the representation of women in Dutch academia remains low.

Role models. In the construction industry, Nataliya rarely saw women in leadership or creative roles — only in technical positions.

“But then, during a business trip to a precast concrete factory in Kyiv, I heard the story of the plant’s director, Svitlana Kovalska. She built her career in a fully male-dominated field — and did so in the 1990s! It was surprising and inspiring.” Now, when I see more female colleagues in different technical research areas, from PhD candidates to professors, I try to learn from them. And their achievements and bravery inspire me as well.

"The higher you climb in the construction field career, the fewer women you meet."

Dr. Nataliya Lushnikova is a researcher and educator dedicated to promoting gender equality in сonstruction. Her professional path spans multiple countries. She has taught in Ukraine, Poland, and Italy, collaborated with the environmental NGO EcoClub, received a scholarship through the Cambridge Colleges Hospitality Scheme, and participated in a United Nations Climate Conference.

She currently works at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e) in the Netherlands, having started her academic path in the Department of Building Materials in Rivne, Ukraine.

This text explores her journey, the challenges she has faced, and her reflections on the structural barriers and emerging opportunities for women in both the construction industry and academia.

Nataliya pursued a technical degree at the National University of Water and Environmental Engineering in Rivne, specializing in Technology of Building Structures, Products, and Materials. Although she faced gender stereotypes and academic challenges in this male-dominated field, she chose to continue her academic path by pursuing a PhD.

“I didn’t see myself in industry: on a cement plant or production line. But the department, where I could do research, felt like a safe space. That’s where my academic path began. I later got a job at the same university, occasionally taught abroad through grants, and eventually moved to the Netherlands in 2023.”

In Ukraine, teaching and research are intertwined; faculty members are expected to write textbooks and tutorials, develop course materials, conduct research, and publish scientific papers in addition to their regular teaching responsibilities.

By contrast, in the Netherlands and across much of the European Union, academic roles can be more specialized or prioritize research over teaching. Nataliya currently holds a postdoctoral research position — a role focused exclusively on research following the completion of a PhD, with no mandatory teaching duties.

To be qualified for teaching in the Netherlands, she underwent a formal certification process that included pedagogical workshops, the development of a teaching portfolio, and delivering public lectures. While the process is more demanding compared with the Ukrainian experience, it offers significantly greater access to resources, advanced laboratory equipment, and opportunities for international collaboration.

“In the Netherlands, PhD candidates often outnumber faculty members. In Ukraine, it’s usually the opposite.”

Nataliya has encountered both implicit bias and structural barriers throughout her academic career.

“During my PhD, I was the only woman pursuing a technical doctorate within a predominantly male faculty and department,” she recalls. “Comments like, ‘Let the man attend the conference — we need more than just a smile there,’ were not uncommon. As a young female lecturer, I had fewer academic achievements compared to my more experienced male colleagues, which affected my teaching hours. After maternity leave, I was suggested to work part-time.”

She later joined an architecture department where women were better represented, which sparked her interest in gender-sensitive approaches to urban planning and universal design. However, the challenges didn’t disappear. When applying for postdoctoral positions, she was met with remarks such as:

“If you get the role, it’ll probably be because of gender quotas.”

Nataliya also notes that gender inequality is not always overt — it can manifest in physical, social, or institutional forms.

“Due to constant changes in university requirements, it took me several years to obtain the associate professor title. I completed the manuscript of the tutorial required to get this position just as my pregnancy reached full term. After giving birth, I kept revising the work — sometimes while carrying my baby up the stairs in a stroller, asking for help or leaving it outside.”

“In male-dominated sectors, women are expected to perform as if they have no other roles, as if being a mother isn't real work.”

While teaching a course on gender aspects in urban planning, Nataliya and her students explored an unexpected link between snowfall and male-centric city design.

"I showed the students a video about a small town in Sweden where, traditionally, snow removal started with the main roads — even though, statistically, those are mostly used by men. Women are more likely to walk, often with children, bags, or while accompanying elderly relatives, so snow-covered sidewalks and blocked public transport stops pose particular risks for them."

Nataliya notes that neighborhoods designed by women often prioritize safety and accessibility. One example is Frauen-Werk-Stadt, a gender-sensitive housing project in Vienna. And in the Netherlands, we see the approaches in urban design that meet the goals of universal accessibility.

Experience. Nataliya’s first step in overcoming impostor syndrome came through a Cambridge scholarship, international teaching experiences, and her work at EcoClub. Her resilience also grew during a visit to Brussels and at a UN conference alongside Ukrainian climate activists. These experiences proved that it’s worth taking on difficult — even intimidating — challenges. Especially those.

Mentorship. Support has been a key part of Nataliya’s academic journey: in Ukraine — through an informal mentor, and in the Netherlands — through colleagues, the Ukrainian community, and the WISE (Women in Science Eindhoven) network. WISE connects women at Eindhoven University of Technology — from PhD students to professors. At first, Nataliya attended events; later, she joined the Board and now helps organize them. Despite progress, the representation of women in Dutch academia remains low.

Role models. In the construction industry, Nataliya rarely saw women in leadership or creative roles — only in technical positions.

“But then, during a business trip to a precast concrete factory in Kyiv, I heard the story of the plant’s director, Svitlana Kovalska. She built her career in a fully male-dominated field — and did so in the 1990s! It was surprising and inspiring.” Now, when I see more female colleagues in different technical research areas, from PhD candidates to professors, I try to learn from them. And their achievements and bravery inspire me as well.

Event Schedule

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur. Sit ut gravida aenean potenti. Metus in eu vel morbi dui nunc tellus. Non a massa maecenas massa.